A while ago I came across a U.S article on the importance of non-profit organizations paying attention to how the law distinguishes between employees and contractors. Here was a topic that seemed timely given all the discussion of new types of work places. I wondered then if there was a Canadian piece on this topic and whether the laws here were similar?

Fast forward. There is and they are. But this inquiry led me to explore several other areas of law that need to be followed by non-profits. The laws affecting organizations are important enough that volunteer boards need to know what key rules affect their non-profit’s conduct. However, boards may not need to know all the details. Read on.

I decided that I would look at four key areas, all in the area of employment law.

- Employees and contractors

- Employment standards

- Human rights

- Occupational health and safety

For U.S. followers of my blog I should point out that the laws in our two countries are quite similar. So this post should be useful to you too.

A companion post, Law 101 for Boards highlights two other areas of organizational law: the duty to collect and submit employee payroll deductions and the importance of keeping bylaws and incorporation and charity registrations current. Law 101 also touches on the matter of insurance. It connects with the law, especially the ones listed above.

I am not offering advice on these areas of law as much as informing boards what laws to pay attention to and where they can get more information. I will suggest that boards need to know a little about each of these areas of law. Executive directors or CEOs, on the other hand, have to know a lot more. Guides to the organizational requirements in each of these areas of law are easy to find and to understand.

It would also seem appropriate here to address the related question of whether a non-profit should have a lawyer on its board? The answer below may surprise you.

Some Basics

More than a decade ago I sketched out a board’s basic legal responsibilities in a 2-page governance guide. The publication’s title, not original by any means, is The Legal Responsibilities of Boards. Their overarching legal responsibilities have not really changed. These are:

- The duty of diligence: this is the duty to act reasonably, prudently, in good faith and with a view to the best interests of the organization and its members;

- The duty of loyalty: this is the duty to place the interests of the organization first, and to not use one’s position as a director to further private interests;

- The duty of obedience: this is the duty to act within the scope of the governing policies of the organization and within the scope of other laws, rules and regulations that apply to the organization.

The focus in this post and Law 101 is mostly on number 3, the duty of obedience. Of course, number 1, the duty of diligence, also applies. So lets take a look.

Employees and Contractors

Given the changing nature of today’s workplaces the distinction between employees and contractors is an important one. There is lots written on it.((The impetus for this whole post was Mike Bishop’s January 14, 2020 piece on the U.S. site Blue Avocado, one of my favourite sources. It is here. There is 2016 piece there also called Ask Rita: Can I Just Hire an Independent Contractor by Siobhan Kelly))

Do you have a person working for you who you consider “self employed” or on “contact”. By this I mean a person you pay wages or a salary to but do not deduct income taxes or CPP (Canada Pension Plan) contributions from their pay cheque? The law has much to say on this.

The difference between an employee and a contractor is not on a continuum. Non-profits cannot move easily in and out of two these employment categories just because a staff person requests it or the board or executive director think “why not”?

So, under what circumstances might a board and/or an executive director want to look closely at this issue? The include:

- The organization has only one staff person and wants to avoid having to deal with setting up a payroll system((A good article on what to consider when you have only one person working for you is this 2015 Charity Village piece the “Solo Employee: How To Succeed When Your Nonprofit Staff Is Just You. by Susan Fish here))

- A staff person works from home or remotely from the “office”

- A staff person is part-time

- A staff person is working on a specific project

- A staff person has their own business

- A staff person considers themselves to be “self employed”

This difference in employment status also has nothing to do with whether the work done is funded by short-term or long-term contracts versus ongoing funding. Indeed, the work of many nonprofit staff members is supported by specific funding arrangements. In other words, a contract staff person is a not defined as a person supported by a grant or hired to do a specific piece of work.

The key legal distinction between an employee and a contractor, or self-employed person, working for you has to do with how much control your non-profit has over the hours work and the way the work is conducted. The rules distinguishing an employee from a contractor are pretty clear. Check out these Canadian links:

- The Canada Revenue Agency lays them out here

- The Canada Revenue Agency publication: Employee or Self-Employed

- Susan Ward, Independent Contractor vs Employee: Which Are You?, November, 2019

- Paul Sharpe, Do You Hire an Employee or a Contractor?, May 2018,

In 2020, If you employ a few people and are of the view that formal workplace relations are in flux, be careful. An executive director/CEO should know the rules. A board just needs to ask.

2. Employment Standards

Probably no single area of law comes more regularly into play for non-profit employers than “labour standards”. These are the main areas of law that covers basic employment matters. In Canada these laws are normally set by Provincial governments. They set standards that regulate:

- Minimum wages

- Deductions

- Overtime

- Vacation pay

- Time off and leaves

- Ending employment (dismissal, notice, etc)

- Employment records

- Hiring of foreign workers

These are all areas than an executive director must know. The good news is that it is easy to find out the key elements of the standards and have the particulars close at hand. For most non-profits it is their provincial standards that apply and the standards from province-to-province differ somewhat but not dramatically. From East to West here is a sampling of labour standards guides:

- Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick

- Quebec (English)

- Ontario

- Alberta

- British Columbia

All 10 Canadian provinces and the NWT have published guides. Some also offer videos, self- assessment tools. Every executive director should have their provincial (or territorial) employment standards guide on their bookshelf or bookmarked online. This is especially because these standards are frequently updated.

There is no acceptable reason, unless the person is new to the job, that an executive director should not have a good understanding of the employment standards that apply to his/her non-profit. Boards should not assume the ED does know them, regardless of the ED’s experience. They should ask.

3. Human Rights

Most provinces and territories have their own human rights commissions and most commissions offer publications and/or training to employers on their responsibilities under these laws. Many websites offer sample policies.

Although some Canadian non-profits are incorporated federally rather than provincially, the job of the Canadian Human Rights Commission is to oversee federal government agencies or organizations regulated federally. Therefore, while the Commission would not likely have jurisdiction over most non-profits, its human rights interests and organizational resources mirror those of most provincial bodies,

An executive director should have a good understanding of the human rights standards that apply to his/her non-profit. Again, boards should not assume this understanding is present, regardless of the ED’s experience. They have the power to make it so.

4. Occupational Health and Safety (OHS)

While non-profit sector organizations have long paid attention to client safety, employee and volunteer safety is new territory for many.

The law with respect to workplace, employee and volunteer safety is less clear in its application to non-profits. This is partly because work in the sector is so varied. OHS resources aimed at non-profits therefore are few and far between. Canada is well behind other counties on this score. However, there are published guides and there are safety associations specific to certain industries, especially in the health care field.

In the last decade, occupational health and safety laws and regulations have been changing to incorporate health issues broader than physical hazards. Psychosocial hazards (e.g. bullying and harassment) are getting more attention. One can add cannabis in the workplace, PTSD and other mental health challenges that employers must be prepared to deal with.

When it comes to OHS education and workplace practices non-profits, like other employers, face the additional challenges of educating young workers and new immigrant workers in their employ.

Non-profits operating in the long term care, home care and disability support sectors face some of the most significant many workplace hazards, not the least of which, as of the writing of this post, is the global Covid 19 pandemic.

Here is a small sample of Canadian OHS organizations all of which offer information for employers:

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (a good introduction)

- AWARE NS -Nova Scotia Health and Community Services Safety Association

- Public Services Heath and Safety Association (Ontario)

- ActSafe Safety Association (B.C.) (Arts and entertainment workers)

All non-profits that employ people should have human resource or personal polices that address health and safety concerns. Certainly processes for reporting harassment and dealing promptly with workplace conflict should be included. And, such policies should be known to all employees. A board will want to inquire on this front too.

Board or Executive Director Knowledge

If a volunteer board was a never changing group and worked many more hours than they do it might be reasonable for this group to know the details of the laws that apply to their organization. This is not the case. The onus on knowing the law sufficient to prevent one’s organization from getting into trouble falls mainly on the chief executive.

This being said, there there needs to be evidence that one’s board has, and is, paying attention.

Indeed, knowing the principles and practices that organizational law reflects can enable boards and executives to aspire to create remarkably good organizations, not just tick off the box that says “we are good here”.

A Lawyer on the Board

It is conventional wisdom that all non-profits should have a lawyer on their board. I suspect that the reasoning is that people see governance as a complicated and legalistic endeavour. Possibly it is believed that having a lawyer around the board table will help keep the organization out of trouble. Neither of these assumptions is accurate. I am not the first to point this out. Here is a good piece, Navigating Not-For-Profits by Len Polsky of The Law Society of Alberta. ((On the subject of having a lawyer on the board one can look at other articles. Some of the issues are well outlined in this blog piece by Jess Birken, a U.S. lawyer. Then there a 2008 piece by Mark Goldstein Reasons to Have – and Not to Have an Attorney on the Board in the U.S publication Blue Avocado. The Law Society of Alberta piece in the text has no date))

A non-profit may at times need access to a lawyer for legal advice but probably that person should not be the lawyer on the board. The organization on whose board a lawyer sits is not the lawyer’s client. Established non-profits should probably have a designated lawyer, a name of a person who they know and who has perhaps done some work for them in the past.

I have tried to make the case above that non-profits, their executive directors and their boards, do have ready access to information on the law. There are lots of good reasons to have a lawyer on the board. They are well educated, like dealing with facts and are vocationally conscientious. In smaller communities they can be well connected too. If a lawyer is passionate about one’s cause, he/she is probably a good board candidate.

However, boards would do well to keep the following in mind:

- Lawyers come in many kinds not all of which have knowledge relevant to one’s organization,

- Lawyers are not beyond giving poor advice, especially where their expertise lies elsewhere.

- Other board members will defer to the opinion of a lawyers (smartest person in the room syndrome)

- Lawyers have a tendency to be conservative when the organization needs to take a risk

- The presence of lawyers can result in the over legalization of many issues.

Keeping Out of Trouble

If your board wants to ensure that the organization is operating within the law it should consider being explicit about what laws must be followed and who’s job it is to know what the law says.

- Policies and Executive Director/CEO Job Description

I believe the first priority in keeping out of trouble is to specify the organization’s key legal responsibilities in policy. For most non-profits, given the four legal issues raised here, the one area where it should look at is at human resources or personnel policy.

I would argue that the executive director’s (CEO’s) job description is also a policy since it too is subject to Board approval. So here is another document where the areas of compliance should be listed. The organization’s HR policy is though a more important place because it is, or certainly ought to be, widely shared within the organization.

These two polices need not contain the specifics of the law but should name the acts or codes in one’s jurisdiction. It is not enough to say merely that the organization “will adhere to the laws and regulations that apply to it.” If one’s policies currently do not address specific compliance concerns they can easily be amended, or a stand-alone compliance policy created.

Here is are some text to add to your personnel or HR policy:

The executive director is responsible for insuring that the organization abides by all relevant laws and regulations and in particular that

- At a minimum, the requirements of the Nova Scotia Labour Standards Code, Human Rights and Occupational Health and Safety Acts are followed

- In hiring the legal distinction between employees and contactors will respected

- Board Orientation

The Board orientation process is obviously another place to alert new directors to the key areas of legal responsibility. You might give compliance matters 15 minutes on the orientation agenda. Clearly the list of compliance responsibilities include:

- Incorporation renewal

- Bylaw update

- Charity renewal

- CRA remittances

- Labour Standards

- Human Rights

- Occupational Health and Safety

Some organizations will have other compliance requirements to add to such a list. Non-profit nursing homes and licensed childcare centres are probably two.

- Executive Director/CEO Hiring and Evaluation

The third vehicle in assuring legal compliance is in Executive Director/CEO hiring and evaluation. A simple question in each assessment might be: what can you tell us about what is covered in the (example) Labour Standards Code? In the case where the person does not know, there is action to be taken and followed up on by the board.

So, How about some comments, eh?

I believe this post will help nonprofit boards see that their organizations’ legal responsibilities are neither mysterious or all-consuming. Indeed, understanding the law affords nonprofits an opportunity to build stronger and more resilient workplaces.

I really hope I get comments on this post. I will be both surprised and disappointed if no one offers up clarifications and additional perspectives to what is a much larger topic. I will certainly solicit some feedback. I am also more than willing to edit the original post to correct something.

If this topic interests you I hope you will come back and check.

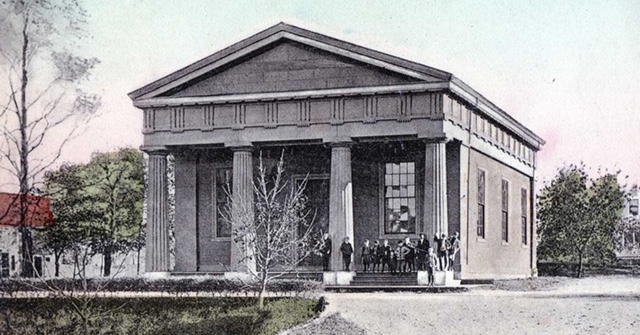

+++ Note on the Image +++

The photo is a turn of the century (19th century) shot of the Liverpool Court House, in South Western Nova Scotia. It is note worthy as an excellent example of Greek Revival temple-style architecture and for its continuous use as a courthouse since its construction in 1854. Court house designs influenced by this movement were often called Temples of Justice, reflecting the fashionable interest in ancient Greece, the birthplace of modern democracy. The building is wooden but the façades have been covered with stucco and scored to resemble cut stones, a technique that is very rare in Nova Scotia.

In 1984 the this Court House was the location of the trial and acquittal of Jane Stafford for the killing of her husband. The case set the precedent for citing spousal abuse as a defense and was the subject of the widely read book “Life With Billy” and subsequent movie.

Here is an image of a portion of the Courthouse interior today.

For a longer description see of this landmark see Canada’s Historic Places, and visit the Queens County Museum in Nova Scotia in person or online.

Grant;

Not all small non-profits have a CEO. My involvement has been with small arts organizations, some all volunteer, others whose staff consists of an artistic director, and if we were lucky, a part-time manager. Who is then responsible for assuring legal compliance? Is it the board alone? These types of non-profits are usually least equipped to have or hire the necessary expertise. What do you suggest in this situation?

Thank you for these interesting articles!

A cultural sector board member and volunteer

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Thank you for asking. It has been said that most board members. when sitting around the board table, are reluctant to ask questions that cannot easily be answered.

If a non-profit has no staff, then it is the board that must ensure compliance. Luckily, most of what I have outlined in Law 102 is not relevant as this post is really about employment law. The exception is probably the area of human rights and I have added an addendum to the post on this topic because it is relevant to fully volunteer groups.

Things do get complicated when there are any employees involved. My intent in both articles is to point out that the board can, with a little study, understand and act on the main compliance requirements of their organizations. The law is not that mysterious.

Organizations with occasional staff might well consider a partnership with a larger organization that could assume the legal responsibilities of serving as the employer, allowing the smaller organization board to advise.

The situation with small arts organizations with staff but no one who is the equivalent of a CEO/ED is a unique one. This is especially so because the artistic director is in a powerful position. He/she may not be unlike the minister, rabbi, or iman in faith-based organizations.

I was not able to find a good article online on this particular issue. There are some resources on artistic director-CEO partnerships such as this short one published by QuickBooks-Intuit Canada and a more newsy or issue oriented one that was published more than a decade ago in the Huffington Post.

I would say that in your situation it is the board who is responsible for legal compliance. The board is both the governing group and a managing one. It may make sense for the managing and governing work to be separated, either by setting up a management committee or having the full board meet as a governing group and then as a management group. Keeping these two hats separate can benefit from written terms of reference for a management committee and separate agendas for each of the two meetings. The terms of reference as a standing document ought to name the areas of compliance that require at least a little attention.

Small performing arts organizations that have artistic directors may want to consider whether her/she, their key employee, would sit on both the management committee and the full board. A good case could be made for not having the artistic director be regularly involved, except by invitation, on the management group. Obviously communication between the two bodies would be important.

It seems to me that non-profits with staff but without a CEO/ED could consider assigning one of their board members to be the group’s “compliance officer”. This is a variation on the idea of board members having “portfolios. Ideally such a post would come with a job description that named the main compliance concerns.

Someone who read this post recently asked me if there were any areas of legal compliance particular to all-volunteer groups, that is, non-profits without staff.

Other than the importance of maintaining incorporation registration described in Law 101 for Boards, and perhaps charity registration, also mentioned in that post, I could not think of others.

I discovered however, that volunteer groups might also be bound by the requirement of provincial human rights codes. Most codes do not specifically refer to volunteers, but also they do not limit “employment” to only paid positions. So, a volunteer can be discriminated against, and some probably are, and may be able to file a complaint. If you are recruiting for a board position or any other volunteer role, pay attention. For more on this see this 2012 article Can You Discriminate against a Volunteer? by Lisa Stam of the Toronto firm of Spring Law.

Grant MacDonald

GoverningGood

Thanks so much for this Grant. As you know we are one of a number of adult literacy organizations all across Nova Scotia. A lot of this work you’ve outlined was on my to do list and will make my job much easier. I very much appreciate your thoroughness and insights with respect to legislative compliance and how to maintain that over time in a nonprofit environment.

Alison O’Handley

Executive Director

Dartmouth Learning Network

Nova Scotia